The Pirates Are Coming for Substack …

But we can fight back

Writer’s Addendum, 1/11/2024: You won’t find the “Hannah Williams” I write about in this post from April, 2023, on Substack anymore, but the risk she represents remains, now boosted by the capacity of generative AI to produce content. It’s easier than ever to simulate a human voice, and thus more important than ever that we seek out and treasure unique, distinctly human voices on Substack and everywhere else for that matter!

I’ve gotten used to the noise, the bullshit, on the big tech platforms.

You know what I’m talking about: the excessive number of paid links on a Google Search, the endless scroll of sponsored crap on Amazon, the flood of recommended or sponsored content on social media (Facebook and Instagram and TikTok).

I’ve gotten desensitized to it: it’s like the ads that air on network TV, graffiti on bridges, litter along the highway, those catcalls I get when I walk by construction sites 😉, or ... well, there’s any number of metaphors for the ways we come to ignore the crap that defiles an otherwise enjoyable experience, crap we tolerate because it lowers our costs. (See a list of related links at bottom that just tickle the surface of what’s been written about this issue.)

But for a long time, Substack has been free of that crap, and proudly, vocally so. It’s been a good place, very pointedly a space where creators—mostly writers, but also illustrators and musicians and more—could connect with their audience in an environment free from commercialism. Okay, not free from it, but it’s a commercialism that seems transparent and “honest”: you publish for free, and you pay the platform 10% of your cut if you take payment (or “go paid.”) No one begrudges that 10%, especially if it means we can create and consume in an environment filled with real people and real engagement.

Many—and here I’m going to speak for a group of creators who I communicate regularly with on Substack—have found real pleasure in using this platform. We have published content that is meaningful to us ... and found people, readers, who enjoyed it and “engaged” with it, not just in the form of likes, but in the form of conversation, shared stories, collaboration. I don’t believe I’m alone in finding these aspects of Substack to be the most worthwhile participation on a public platform I’ve ever experienced (and when I say “ever,” I’m old enough to speak as someone who has participated on those platforms almost since they began: I used Mosaic before it became Netscape Navigator.) Nothing I’m about to say diminishes the value I find in these community aspects of Substack. But there’s trouble brewing here in paradise.

One of the pleasures of the Substack community is the high degree of trust that we’ve had that the people we engage with are, well, people. We knew they were people because we could reply to their comments and they would reply back; we could visit their Substack pages and could see pictures of them (or at least, pictures of real humans); we could write to their email address and they would respond. Oh sure, there were occasionally some oddballs—hiding out in the Central American jungle, no doubt—who tried to hijack our posts to boost their own work, but Substack makes it pretty easy to block or delete trolls and the like.

What we didn’t experience was “bots” or scammers. But that’s begun to change.

VB3 Writes Bullshit

In November of 2022, I picked up a new subscriber who liked a bunch of my posts. But “he” had a weird name: VB3WritesFiction. So I went to check out “his” Substack and it felt like the entire Substack—a bunch of fiction and nonfiction—was the product of a non-person. The writing was utterly devoid of a human voice. I’d felt this with chatbots and seen its early stages elsewhere, and now here it was in Substack, surely not for the first or the last time. I emailed “him” and told him I thought “he” wasn’t writing any of this stuff; “he” wrote back and said “he” was.

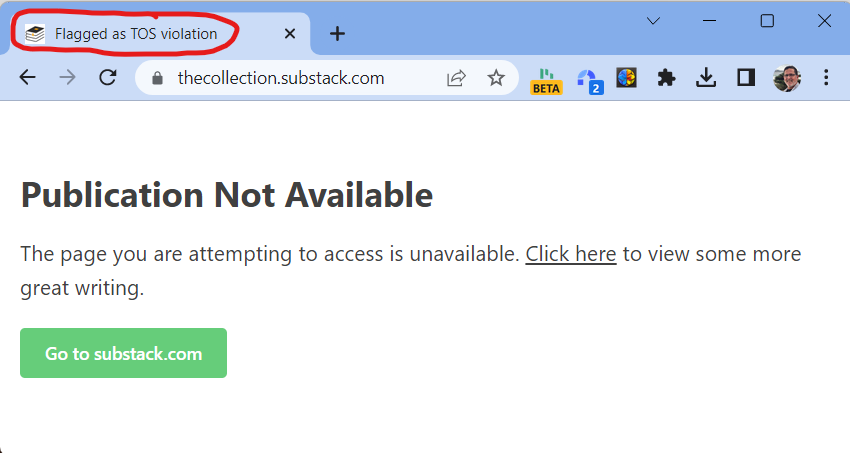

But search for VB3WritesFiction today and you’ll find only “his” ghost: the Substack site is gone, the community created in that name on Reddit has been banned, and “he” exists only in dead links in a Google search.

Lately, however, there has been another ghost floating around the periphery of my Substack world. About a month ago (March 2023) someone named “Hannah Williams” began to like the comments I had made on other Substacks ... a lot! This was not a subscriber of mine, and as yet they had not liked one of my posts directly. But I was curious, so I went to check our “her” site, The Collection, and from there to “her” profile: Hannah Williams | Substack.

I even wrote to “Hannah.” Here’s what I said:

Hi there,

I noticed that you’ve liked a number of my comments on other Substacks. Really appreciate that, as I suspect it boosts me in the recommendation engine.

Is there something you’d like me to do in return? I notice that you don’t comment yourself, just like stuff. Is that by design? I’d love to hear your strategy.

Tom

I didn’t receive any reply, and (like a good journalist) would be happy to correct anything I’ve gotten wrong.

Let me cut right to the quick: I don’t think Hannah is real, nor do I think there is a person who is writing the book summaries that are the sole output of this “author.” (Duh, you may say: look at “her” picture.) I surmise that “Hannah” is the creation of someone—I’m going to call them a scammer, though we can debate the term—who wants to attract a bunch of traffic to their site and has figured out how to hack Substack’s internal API or other code in order to place likes on comments, thus encouraging those whose comments are liked to subscribe to Hannah’s page, driving up her “subscriber” count.1 The content they create is generated, I suspect, using one of the suddenly ubiquitous LLM2 text generators. They use it to summarize popular books, thus offering readers a shortcut to the “most valuable aspects” of these books “in an easy-to-read and short format” (I'm quoting from “her” About page.)

What the Scammers Are After

So what’s the point of these scams?

The point, it seems to me, is to generate a huge subscriber count—because high subscriber counts are the currency of influence in the corrupted land of influencers—and then to parlay that influence into money, either through paid subscriptions (though we can’t know how many of those there are) or—and here’s where I get worried—by using that subscriber list to launch some other money-making scheme, either legit or illegitimate. Sounds familiar doesn’t it? It’s the standard-issue Internet scam we’ve been living with for years.

And why does it work?

It works for the same reasons, and via the same human dynamic, that all scams work: by preying on human vulnerability. Who isn’t flattered when a “pretty girl”—hell, when anyone—likes what they said? Even when they are obviously not real! (You don’t have to be testosterone-addled to be susceptible to pretty young girls: such appeals are directed across the gender-identity/hormone-balance spectrum). The truth is, we all want to be liked—it’s at least partially why we write and comment on Substack in the first place. We want to connect—and look, this person likes us! We pay attention to those who pay attention to us ... even if they’re not real, even if they’re only paying attention to us in order to exploit our reciprocated attention for their profit.

Do we see here the first seeds of “corruption” that will drag Substack down into the same cesspool that has spoiled the early promise of every other tech platform? Or should we take the rapid correction as a sign that Substack is serious about fighting such “corruption”? Time will tell, but I’m encouraged to see that Substack is already acting against this abuse.

I don’t have a single solution to this problem, this quintessential problem of our age ... but I have a couple suggestions, and I’d be curious to hear what others think.

1) Let’s all be more skeptical of who we engage with on Substack (like we should be EVERYWHERE else). Think twice about subscribing to or recommending anyone; at the least, verify as best you can that they are a legitimate creator. It is not in our interests to allow scammers to inflate subscriber counts to their benefit and at our expense. (Nor is it in our human interests to value the output of AI more than the output of fellow humans; indeed, it may be our downfall.)

2) We owe it to each other to report suspected “abuse” to Substack at tos@substack.com. It may be that such a report was what led to the removal of “Hannah Williams” from the platform; I don’t know. I do know I don’t support harassing “suspected” violators, which is why I tried to open communication with “Hannah” before writing this piece and would have first contacted Substack—if the account hadn’t disappeared as I was preparing this essay.

2) Substack needs to scrutinize its code to make it more difficult for scammers to exploit that code to generate undue influence.3 (Their security team is likely highly protective of personal information, especially payment information, but perhaps not about the means by which scammers can utilize their system to gain access to influence.)

I want to thank the following real people who have contributed to my understanding of this issue via conversations sparked from real engagement on Substack:

Some reading on why tech products get worse, not better, and internet scams. (If you’ve got additional links for this list, please send them and I will add them to the list):

Ed Zitron, “Big Tech’s Big Downgrade,” https://www.businessinsider.com/tech-companies-ruining-apps-websites-internet-worse-google-facebook-amazon-2023-3

John Herrman, “The Junkification of Amazon: Why Does It Feel Like the Company Is Making Itself Worse?,” https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2023/01/why-does-it-feel-like-amazon-is-making-itself-worse.html

Cory Doctorow, “The ‘Enshittification’ of TikTok: Or How, Exactly, Platforms Die,” https://www.wired.com/story/tiktok-platforms-cory-doctorow/ (also here: https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys)

Adam Pasick, “Artificial Intelligence Glossary: Neural Networks and Other Terms Explained,” https://www.nytimes.com/article/ai-artificial-intelligence-glossary.html

Alex Goldman, “#102 Long Distance,” https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/6nh3wk/102-long-distance (part one of a two-part podcast on phone scams)

Which would be a violation of Substack’s terms of service, spelled out here: https://substack.com/tos

Large Language Model. There’s a good glossary here: https://www.nytimes.com/article/ai-artificial-intelligence-glossary.html

It’s beyond me to explain how, but I know it can be done.

I saw all those Hannah Williams likes on my posts over the past couple of weeks and thought I was trending. Damn you, Tom, for crashing me back to Earth.

This might be the most timely post I’ve ever read here.

Over the past few days (maybe a week?) I’ve been receiving an absolute flood of likes from our “mutual” friend. The strange part was the quantity/rapid succession of likes (and these were from comments I left on different writers’ Substacks! Not even my own posts!) I was about to reach out to her to see what the deal was. Glad it’s been handled!

Over the past two weeks I’ve had two different new subscribers sign up. On both occasions, following my subsequent post, they disabled their accounts - yet opened my emails upwards of 700 times. After the first one I thought maybe it was a fluke...but after the second one, I’m going to flag those email addresses and alert Substack about it.

Thank you so much for the post! Hopefully we can rid Substack-land of these scammers before it gets out of hand.