I’ve walked in Snohomish, Washington, for 25 years. For the longest time I’d run into friends from town and the first thing they’d say was: “I saw you out walking.” That’s just what we did. Mostly we did our 4-mile loop: up the hill to 13th street, around and down to the river, along First St., then up Avenue J to home. We did our 3-mile loop when we were short on time, and, when we were feeling more ambitious, we’d tack on Pilchuck Flats, heading east across the Sixth St. bridge and looping back on the Centennial Trail.

But for all that walking, we rarely went out beyond the water treatment plant. I took the kids out there once, many years ago—they must have been like 5 and 7—and we bushwhacked across the high grass toward the river. I learned later that we had walked across a field full of "unscreened biosolids” that had been deposited in what had been a lagoon from 1958 to 1995. Yuck.

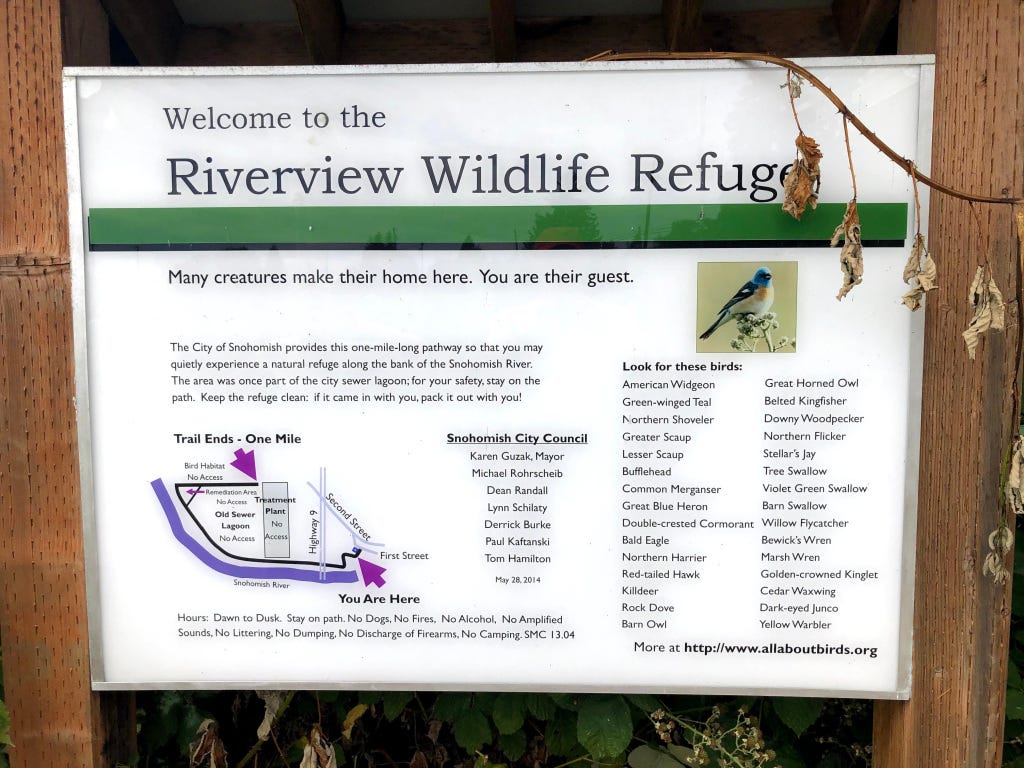

The city shut their old school wastewater operation down in 1995 and pumped their effluence west to Everett, shutting down the lagoon. That made the local birdwatchers happy. They adopted the periphery of the abandoned lagoon, and convinced the city to support making the whole area into a wildlife refuge. Their master plan, submitted to the city in 2013, renamed this area the Riverview Wildlife Refuge.

You’d have thought that the designation as a wildlife refuge would have drawn me in. But I’d closed my mind to the area. I considered it a marginal re-use of city land, blighted by the proximity of the city yard on the east end, by the Highway 9 bridge passing overhead, by the treatment plant.

The truth was, I had gotten a little stuck. I’d stopped looking for new places to explore. I’d gotten sucked into devoting most of my brain space to work, work, work. The money was nice; my life, not so much.

Then, everything changed.

On March 7, 2020, I stopped going into work. So did Sara. So did a lot of people.

I still worked, just from my upstairs office, and now I didn’t have a 30-minute commute and I didn’t need to shower unless I wanted to. My schedule had been flexible before; now it felt wide open. I had so much more time ... and so did my neighbors.

I could tell because on warm spring days, the streets filled with walkers: middle-aged couples, whole families, teenagers, all home from work and school, all strolling out in the spring sunshine in the middle of the day, smiling, chatting, walking down the middle of the street, now free of cars. The pandemic was still young and new in those days; there were no masks yet, no social distancing, no politics. It was a big adventure. We all smiled and said hello to each other, neighbors we’d seen but never really noticed much before.

I’m all too aware of the dark side of the pandemic. The death. The toilet paper shortages. The masking. The suspicion: Why wasn’t he wearing a mask? Why is she still wearing a mask? The politics. Ugh.

But this was the bright side, the silver lining. Work sat more lightly on my shoulders, and as I found time to step outside for a mid-day walk, to take lunch with Sara on the back porch, I began to see the world differently, as more open, more full of possibility. Maybe it was because the stress of worrying about catching a deadly disease put the stress of work in context, but I swear, the sun felt brighter, the air smelled of flowers coming into bloom. Life seemed sweet. I breathed more deeply. I opened my mind to it.

And then there were the birds! I’d always been a birding skeptic, a birding contrarian. I was the guy who mocked birders. I’d say “There are only three kinds of birds: killing birds, water birds, and little brown dicky birds.”

But then Jeremy Schwartz, the sweet, sensitive guy from the marketing team, did a birding talk for our company. It was a Zoom call, of course; we were all still working from home.

Jeremy introduced us to three birds we could probably see on any given day, and he told us about their coloring and their sounds and their habits. It was like he pulled back a curtain, because after that talk I saw birds EVERYWHERE. I could hear them in the trees, chattering happily. It wasn’t long before I put up a bird feeder and downloaded an app to help me ID the birds. “Look Sara,” I’d say, “it’s an American Goldfinch.”

The conditions must have been just right: the pandemic, the sweet feeling of time opening up, the birding, and this sudden openness of mind. Because one day we walked down our street and, instead of turning left, toward town, like we usually did, we turned right. We walked under the highway, so quiet, and then out behind the water treatment plant. And that’s when the world changed for me.

That’s when I discovered Vetucchio.

Maybe it was the fog that made mornings feel so magical, the fog that lifted slowly from the ponds that lay beside the dirt path that skirted the chain link fence and led us out toward the Snohomish River, the grassy basin on our left, the marsh on our right. Maybe it was the bird calls: the rising conk-la-ree! of the Redwing Blackbird, or the witchety-witchety-witchety of the Common Yellowthroat, or maybe even the fitz-bew of a Willow Flycatcher, coming from high in a tree.1

Maybe it was the way the fading afternoon light stretched across the valley and lit up the grassland and the tall cottonwoods, their trunks bright against the darkening sky. Maybe it was looking through the metal fretwork of the Highway 9 bridge to see the snow-covered flanks of Mt. Persis and Mt. Index in the distance. Maybe it was the rumble of the freight trains just across the river, sounding their horns as they reached the refuge, warning the town ahead.

We walked here again and again, and I fell under its spell. I’d time my walks to catch the morning fog, to watch the blue herons flying away from their rookery like the dinosaurs they were. I’d walk again late in the day, relishing the sumptuous evening light. In August, I’d walk here every day, filling myself up on blackberries.

How had I missed it all these years? What damn-fool absorption in work or money or “important things” had kept me from seeing the beauty that was so close at hand?

No one would mistake me for a romantic, but my attachment to this place felt like nothing I’d ever felt before. I wanted to give this place a name that lived up to the spell it cast over me, so for days I rolled the sound of various words around in my mouth as I walked, remembering the feel of the Italian hillside we had explored, and the towns along the Amalfi coast: Ravello, Positano, Sorrento. I wanted a name that was melodious, evocative. And that’s how I came to call this place Vetucchio.

Vetucchio! Vetucchio!

I go out there now, three years later, and I can still see why I fell so hard for the place. But I also see that Vetucchio is more than a place, it’s a moment in time when I opened my eyes to the beauty of things small and subtle and close at hand.

It’s not just a place; it’s a state of mind. And it’s just down the road. Vetucchio!

Here are a few more of my favorite photos from Vetucchio:

I’m using the sound descriptions offered at All About Birds, though mine would be ever so slightly different. Is it me, or do my local birds have a slightly different accent?

Love the photos. Urban living is great when there are pockets of wildlife. Only today we discovered that our local park, which we walk or cycle in at least once a week, has deer and a muntjac. I'm so glad you have discovered Vetuccio!

Well written !

Here's mine = It is an ideal place for a gentle walk or for wildlife watching.

In the past it was covered with coke and coal waste and crossed with mineral railways lines. It is now home to grassland birds, including lapwing and skylarks, and the water rail. https://www.northlanarkshire.gov.uk/directories/local-nature-reserves/dumbreck-

Salmon have returned to the Garrell Burn in Kilsyth for the first time in 100 years, as a result of a river restoration project by the council and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA).