Stamper's Big Project, Part 1

Chapter 6 in my ongoing story about workplace surveillance

< Previous Chapter | First Chapter | Plot Summary | Next Chapter >

As intense as Kate Stamper was with guys, she was even more intense about her work.

She was hands down the best instructional designer I had ever seen, and that in a company that prided itself on hiring the best. All our instructional designers (we called them IDs) could create strong courses that met and exceeded the requirements; we had a wall of awards to prove it. But Stamper took it to another level.

For her, every client project was a personal challenge. It wasn’t enough for her to be the best ID. That was easy—a simple matter of learning objectives and clear communication. No, she was looking to get at some deeper truths about how humans learned, and how to convert learning into behavior. She wanted to create online training that amused, entertained, influenced, and ultimately changed how people acted. So every new project was an opportunity to perfect her craft. She reminded me in some ways of a superstar athlete: a Michael Jordan, Lionel Messi, or Serena Williams. Like them, Stamper wanted to do more than show mastery of the essential skills; she wanted to redefine the sport.

In order to get these chances, Stamper needed to work with our top clients, the ones with the money and imagination and ambition to support her goals. She needed to play in the championships. So what if her elbows sometimes got a little sharp when jostling for assignments? She didn’t care that her attitude put her at odds with some of the other IDs (and neither did I). Theresa and April had been there for years when Stamper showed up. At first they were determined to keep Stamper from the good assignments, insinuating that her work wasn’t good enough and currying favor with the previous ID manager, Nels. They complained that she was too brash, too pushy—but all that did was fire Stamper up. Nels and I could see that Stamper’s work was just of another caliber. We didn’t want to play favorites—but Stamper got all the good assignments because she was obviously the best. When Michael Jordan is on your team, you get him the ball.

Once she was engaged with the client, Stamper was a force of nature. She’d wrap the client in her attention, probing for the most interesting things she could find about the subject at hand, challenging them to be more daring in their ambition. Each new project, each new client, was a mountain to climb, a heart to win, a heathen to convert. I worried sometimes that she scared people. She’d ask a question like, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could just get inside your employees’ heads and flip the switch that made them behave the way you wanted?” and look the client in the eye for just a beat too long before laughing it off. She took people right up to the edge. But man, they appreciated her intensity and her focus on quality. Once a client of ours worked with Stamper, they shunned other IDs. None brought the commitment, the fire that Stamper offered. She made our clients feel like they mattered, like their work mattered.

Winning over a bevy of adoring clients, sidelining the colleagues who questioned her–this satisfied Stamper for a while, but I sensed it wouldn’t hold her interest for long. As her manager, I started to worry that she was getting bored, that I’d lose her as she went off to chase something more interesting. As her colleague and friend, I just liked playing the game with the best, and she was the best. So I was pretty happy when she returned from a long Christmas break all fired up about her big new idea.

“Dan,” she said as she rushed into my office, closing the door behind her, “I’ve got an idea about how to revolutionize our training …”

“Well hi, good to see you too,” I laughed. She had burst through the back door and marched straight to my office like she was on a mission. “Did you have a good break?”

“Oh yeah, yeah, fine, fine, whatever,” she said, batting aside my small talk and diving headlong into telling me her idea. “But listen, I read this book about how Google built their ad delivery business, and then I was also thinking about what Apple is doing with music, and I think we can blow apart the training industry if we can just pick up a few things that they’re doing. But it means we’ve got to change everything we’re doing: we have to think about training in totally different ways, we’ve got to figure out exactly what people know and don’t know, and what they do and don’t do, and then we’ve got to deliver tiny little learning units—screw these long courses!—that really get people to change their behavior and we’ve got to measure it and if we can do this, like really prove we can do it, we’re just going to kill it.”

“Holy shit Stamper, that’s a lot to take in on the day after vacation!”

“Look, you know I’ve been getting bored and frustrated, but that’s because I’m sick of doing stand-alone courses or curriculums that are disjointed from all the stuff employees need to do. It’s the same old shit over and over. I mean, we build nice stuff, but then we give it to the clients and it just disappears. Our clients don’t even have the tools to understand whether their employees are doing what they want. I want us to identify on a really detailed level what we want people to know and do, and then I want to track how well they’re doing it, and then we can prove to everyone that we can really get them the results they want. That means we’ve got to break behaviors down into the smallest possible units and then identify those behaviors and distribute targeted training content just to the people who show they need it—like Google delivering ads to people based on their browsing habits, or Amazon recommending ads based on your past buying. I want to build a whole system to identify and change behavior! Don’t you see how cool that would be?”

“I do!” I replied, and how could I not—she was out of her mind with excitement.

“Can we do it? Can we do it?” She was laughing, playing, but she was serious too.

“I think I have to understand it before I say yes!” I said.

“Oh you’ll understand it, I just need to break it down a bit more and I need you to do that thing where you ask me a bunch of questions, get me to slow down …” And with that she turned to the whiteboard in my office and began to sketch out her vision. She didn’t ask if I was busy—she just got to work.

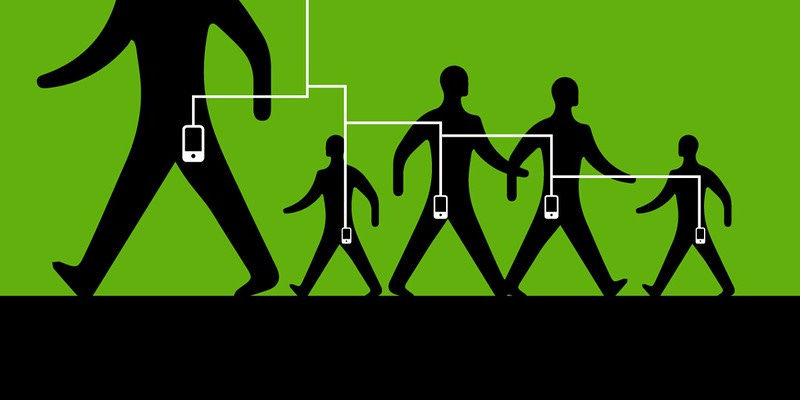

Here’s the nutshell she laid out for me that morning. In her new world, employees would come in and do their work, interacting with all the tools they always interacted with: they’d log in to their computer, check their email, send documents, IM their coworkers, use their smartphones, interact with various software systems … normal work stuff. But as they did that, they’d be revealing how well they understood things like cybersecurity and privacy (our traditional area of focus): they’d reveal the strength of their password, their ability to detect phishing and spam, their understanding of what data should be protected, etc. Basically, without even really knowing it, they’d be creating a “profile” of who they were, a risk profile. And once we had that profile, we could assign them only the training that was needed to improve their performance (instead of stuff they already did well). Then we’d keep profiling them, and that would allow us to see if they improved or not. If they didn’t improve, it was either because our training was no good or the employee was intentionally negligent. Either way, we could do something about it.

“But it doesn’t have to stop at the boring cybersecurity and privacy stuff we’ve been doing,” she said, warming to the topic, though she had already started red hot. “There’s just so much more we can learn about people from the way they interact with the digital environment: when they log in, how focused they are on their work, what kinds of language they use. I mean, like wage and hour stuff, HR stuff, policy and regulatory stuff—there’s no need for us to drag everybody through a whole bunch of training if we can just observe what they need and only train them in that!”

“You know dragging people through training is the whole purpose of our company, right?” I asked, half amused, half wary now.

“Yeah, I know, I’m not saying we don’t create training … uh, wait, I am saying that. I mean, our job isn’t to ‘create training,’ right, cuz that’s just too boring. Our job is to deliver the changes in behavior that our clients want. When they say, ‘train my employees,’ they’re really saying, ‘make my employees behave differently.’ I’m just saying we have to go at it in a totally different way, like top-to-bottom different. Dan, wouldn’t it be great if you never had to take ‘required annual training’ ever again? I hate that crap! Everybody hates that crap. And it would also be great for our clients, because think of all the time people spend in training that they could spend actually doing real work, and how much they resent that time. And if we actually change behavior, instead of just assigning courses, well …”

“But what are we going to do with all the training we’ve already built?” I asked. “We can’t just throw it all away. Companies have invested too much.”

“Oh yeah, sorry, we’re going to have to blow it all up and rebuild it,” she said. “But once we do, it’s going to sell like hotcakes and we’re going to be huge.”

I won’t deny it, my reactions were all over the map. I was scared at how big it was, all too aware of what it would cost to “blow it all up and rebuild it.” I was worried we didn’t have the know-how to do it, worried that our CEO, Mike, with his go-slow approach to everything, wouldn’t allow us to do it. I was also excited at the prospect of tackling a project this big, this audacious. But you know what excited me the most? Stamper had a big new goal, and she was talking about “we”—and that meant she was staying. Stamper was kind of scary, but not when she was on your team. Then she was exciting.

“All right,” I said, “I’m in.” Little did I know where it was all going to go.

< Previous Chapter | First Chapter | Next Chapter >

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction. I’ve made up the story and the characters in it. While certain businesses, places, and events are used to orient the reader in the real world, the characters and actions described are wholly imaginary and any resemblance to reality is purely coincidental.

Wheeler!