Pacing Our Way Across the American West

Reflections on time and mental models, gathered on a recent road trip

Ever since arriving in Albuquerque I’ve been thinking about how we construct mental models to understand the environment we live in, and how things like pace and distance and familiarity impact those models. Consider today’s piece a trial balloon (and if you hate it, please, shoot it down!)

As we entered the home stretch—the long, gradual grade down into Albuquerque—I noted a profound discontinuity between my physical and mental states.

My body felt one way, my mind another.

Physically, I was shot. I felt like I had been tied to a rack: five straight days of driving, 2200 miles in all, had locked my hips and back into early-onset rigor mortis. Despite our daily stops for walks, by mid-day each day, all I could feel was stiffness. During the rare times we stepped from the car I lurched about like my tendons had been drawn too tight.

But my mind, oh god, my mind! Moving quickly through space—simultaneously piloting the Swedish-made, Maple Brown road-trip machine we call “Rootbeer Float” and marveling at the shifting landscape—my mind felt alive, nimble, flexible. I had to concentrate, sure I did, especially when the roads got twisty, but I could also muse, imagine, and—like a hummingbird dancing across a field of flowers—flit across the living, moving landscape. My body may have been imprisoned behind the wheel, but my mind danced and weaved across the mental model I had been building of the American West, a model I’d been noodling on in earnest for two years, not to mention all my life.

Ever since my parents first packed up our family and took us across the country from our home north of Detroit, Michigan, to see what we then called “Out West,” I’ve been enthralled with the landscape of the West—the mountains, the valleys, the rivers, the ocean, the vastness of the empty spaces. Growing up, we traveled across the continent by train (Canadian Pacific, from Toronto to Vancouver, then the ferry out to see my grandparents on Salt Spring Island), by car numerous times, and by plane. I was such a sucker for the West that when it came to choosing where I went to grad school, I declined my acceptance by Wisconsin and Emory and chose Washington State University! Once I had a family, we moved west, sampling Albuquerque for a year before settling in the cooler, greener climate of Washington. I’ve lived in Snohomish, WA, for 25 years now.

Since living “out here”—isn’t it funny that I still think of it as “out here”?—I’ve seen a lot of the West. For work and pleasure, I’ve flown between Seattle and nearly every Western city. These flights offer an aerial view for my mental model of the West. Afforded slightly more time, I’ve also taken numerous trips on the Interstates. These trips brought me closer to the land, showing more of the contours, but they still left me hovering over the surface. And of course I’ve spent a lot of time on foot, climbing mountains, running trails, and walking, walking, walking—but the pace of human-powered locomotion means these are very local views. Together, they inform this living, breathing model of the world I carry in my mind.

But two years ago, we began to practice another way of exploring the West, and it’s adding great richness and depth to my model.

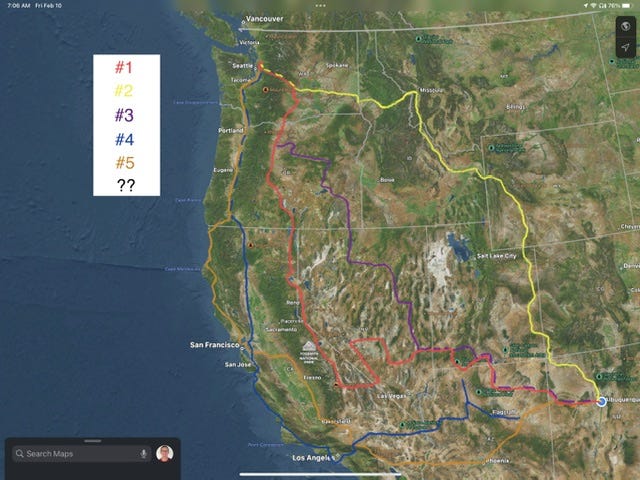

Two years ago, when I extracted myself from the bullshit machine after four years of watching a dream die, Sara and I realized that we now possessed something that we’d never had before: vast amounts of time to do what we please. No longer would we owe our first allegiance to our jobs; no longer would we need to carve out from those jobs small blocks of time to enjoy. Now, we could take all the time we wanted to do as we wish. With more time, we could slow our pace. And the very first thing we decided to do was take a long leisurely road trip from Snohomish to Albuquerque, avoiding the Interstates and taking the back roads. (Our first drive is identified as #1 on the map below, and the drive we just completed is #5. We’re musing about how to structure #6, our return trip, now. Odd trips go south; even trips go north. All road locations are approximate.)

Freeing ourselves from the Interstates added time, but who cares? It reduced tedium and added wonder. Interstates bully the landscape: they flatten hills and straighten curves and self-importantly avoid small towns. Interstates insist on creating a predictable driving experience so that drivers can move through space as quickly as possible. They are an experience in themselves, the same in the plains as they are in the mountains, in the city as in the country. If all you want is the fastest path between Point A and Point B, take the Interstate.

Secondary roads embrace the landscape, floating up and down, left and right, they partner with the terrain, finding a path through hills and valleys and canyons that puts you on intimate terms with the land. And they go through towns, connecting up the main streets, forcing drivers to slow down and maybe even stop. When you take the secondary roads, you must slow down and experience the world more intimately.

It’s not the roads alone that transform the experience, it’s the pace they compel, the way they force you to take more time to experience the world. Slowing down, you see more … and yet the pace of driving and the requirement that you pay attention to the machine you’re piloting still require you to stay on the surface. If driving on the Interstates feels like using a JetSki to cross water, taking the secondary roads feels more like surfing: sensing the undulations on the surface, rising and falling and dipping with the land.

I was reminded of the shock I experienced when I took up birdwatching. Birdwatching compelled me to slow my usual headlong walking pace to a crawl, the better to observe the birds. But in slowing to a crawl, I paid so much more attention to the details everywhere in the landscape. Throttling my speed, I became more of a naturalist, less of a conqueror. (My buddy Jeremy goes slower still … but I can’t do it!)

These realizations about pace make me wonder what I might discover if I slowed my pace of travel between these two points yet again—if, for example, I did a bike trip from Snohomish to Albuquerque. How much better would I understand the world as a result? What would that add to my model? (And hell, what if I walked!?)

I imagine to myself that if I sampled this land at enough different paces, and via enough different routes, my mental model would get good enough, detailed enough, that you could drop me anywhere west of the Rockies and within a short time I could figure out where I am. Wouldn’t that be cool?

That’s the kind of nonsense I delude myself with as the miles pass by … it’s so different from the close study and observation with which I often occupy myself.

Now that we’re here, just a short walk from the Rio Grande, I’m eager to go very slow—to patiently tread the miles of acequias1 that surround the house where we’re staying; to walk every inch of the bosque2 that lies along the river; to listen to the chortling of the Sandhill Cranes; to spy the porcupines sleeping in the branches of the cottonwoods; to note the magical way that the shadows are somehow sharper here in the Southwest sun. There’s beauty in going slow too, and I’ll go there next.

Is there a world you want to understand? How big or small is it? And how do the ways you approach that world—the pace at which you travel, the angles you take, the tools you use, the people you share it with—change how you understand it? I’d love to hear from you!

Next week or the week after, I’ll report on my slow study of the acequias in Albuquerque. Teaser photo below, and one of the nicest things I’ve read about AI yet:

The simplest definition of acequia is “irrigation ditch,” though I prefer the richer “community-operated waterway.”

Again, the simple definition is “small wooded area,” though my experience here is all towering cottonwoods lining the Rio Grande.

Really interesting post, Tom. One thing I'd like you to explore more along these lines is the conflict between your tired body and active mind. The piece sets that up really well but I think there's still room for more exploration.

Also, is creating these kinds of "mental models" possible because you're not 25 and in a rush all the time? Is it natural to "see more" as you get older? Or, is there a way to train your brain to slow down even while your body and work and kids and etc. etc. etc. are saying "Go, go, go."

I really love this piece Tom. I envy your lifestyle. Slow travel is the only way to do it. I particularly love your line about the interstate bullying the landscape. So true. Thanks for sharing.