“My Dad” Follow-Up

A quick break from our regularly scheduled programming to follow up on that last piece ...

When I wrote that last piece about my dad, who died in 2015, I felt done with the subject.

And then so many of you responded! In the Substack comments section, on Facebook, and via a bunch of direct messages, I learned that many of you have troubled, even tortured relationships with your fathers. Clearly, none of us are alone in this!

Of course, I may just have been hearing from those who recognized the pain—and not from those who have warm and supportive relationships with their father. And, so I’m curious: are my most of my readers in this boat with me, or floating alongside in a more comfortable one? Please take this one question survey and I’ll share the results soon.

The conversations I had with you made me wonder: Why did so many of our fathers (and some of our mothers) have such a hard time staying connected with their children? Were they simply unprepared for the commitment that a long-term parenting relationship requires? Did divorce or job loss or alcoholism or something else throw them off course at some point? And did they ever get a second chance?

I wish my dad had lived long enough—and our relationship had healed enough—that I could have asked him some of these questions. I did ask him … no, I begged him to tell me why, why did he “abandon” me right as I was starting a family of my own? His answer—“I just have to protect myself”—rankles to this day.

Some of my childhood friends mentioned that I hadn’t described the guy they knew—and they were right. After all, they knew the fun, loving, decent dad who I grew up with, fixed cars with, chopped wood with, watched football with.

They didn’t see nor live with the mounting difficulties in my parents’ marriage, the bitterness and petty cruelty that made me, for a time, swear that I would never marry. (Six months of living with Sara convinced me it wasn’t marriage that was the problem; it was who you were married to!)

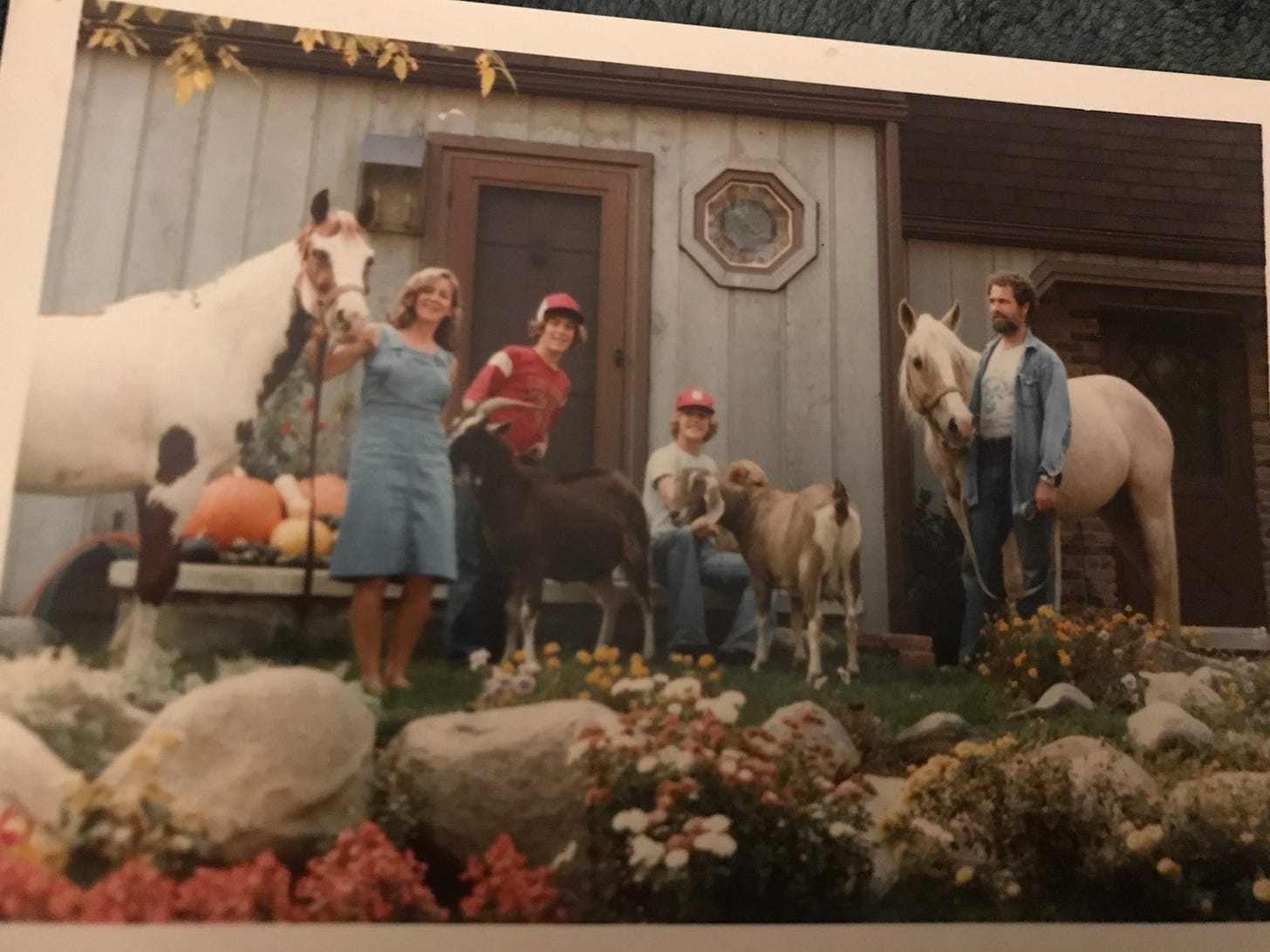

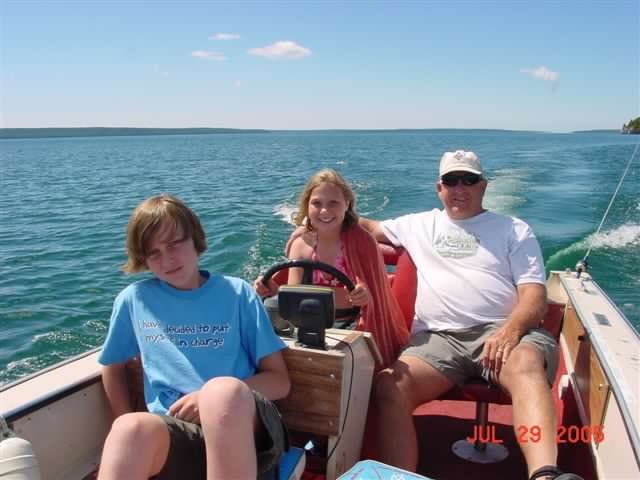

I was lucky enough to have another father figure in my life, my step-dad, Lee Van Wormer. Lee got a second chance when he met my mom, because he too had botched his first run at fatherhood (for reasons only his wonderful kids could explain). My brother and I didn’t need a dad and Lee didn’t try to be one, but he was a solid male figure in my life, a great husband to my mom, and, to his great credit, a wholly engaging and loving grandfather to my kids. I’m so happy my kids had Grandpa Lee and I really believe that Lee felt like he was getting a do-over with my kids, a chance to do well at something he had done poorly before. Man, I miss him every day!

I wonder how many others saw a failed father get a second chance? My own dad had a second chance with Judi’s family. As Pete and I sat at his memorial service and listened to members of her family talking about what a loving, connected father and grandfather figure he was, we just looked at each other with shock: we hadn't known that guy since we were teenagers. He'd been dead to us since our parents' divorce. But clearly, our dad had found a way to make amends with his new family. Good for him. I bet that felt a lot better.

I would never have chosen this nasty turn in my relationship with my dad, but I long ago determined to learn from it, to make the best of it. Much of what I’ve tried to do as a husband and a father is a direct result of—hell, a direct and conscious renunciation of—what I learned from my father. While I take from my dad an intense curiosity, a real love for John Prine, and a troubling fondness for potty humor, I do not carry on his patterns with loved ones. I’m committed to being there for with my loved ones—my wife, my kids, my friends, my extended family—and to sticking it out when things get hard. I’d do just about anything to keep those relationships intact and healthy.

That’s all we can do, right? Try to learn from the mistakes we make and the mistakes we see others make, try to be the best people we can be.

Thank you again for letting me share this stuff with you. I write because it’s useful for me to examine my life, and I read the writing of others because it helps me understand the world. The conversations with you are the icing on the cake!

Here’s that survey again, in case you forgot:

As always, if you like this please subscribe or share with someone else you think might like it. Subscribing is free—it just means you’ll get this in your email or in your Substack app. I don’t expect to run a paid subscription anytime soon! I send something once a week, with rare exceptions (like this one).

Since I met you Tom, your radical honesty and self-acceptance has always had a way of inspiring some parts of me I don’t pay attention to to speak up. I don’t know if that makes any sense, but I appreciate that about knowing you Tom.

Maybe when there is deeply troubled bonds in immediate family relationships, especially with parents, maybe there is a metaphorical fire that comes from all the distraught feelings. Some of us are lucky enough to see that fire, and know we have a choice what to do with that fire inside us, that fire we didn’t ask for. It sounds like you used your fire to light the way for your future, which is what we all want our parents to do, just ironically, not by leaving us with a fire and no clarity about what to do with it.

Many years ago now, my younger brother, a folksinger, summed up our feelings on this subject: "I was our father was Pete Seeger."